Aquí podéis escuchar la conversación que tuve con el maestro zen, Dokushô Villalba el 27 de Diciembre de 2021, sin ningún tipo de edición. Quizás si algún día me decido y hago esto oficial ya le pondré musiquita e intro. Si seguís haciendo scroll, podéis leer más sobre el proyecto.

Here you can listen to the conversation (in Spanish) I had with Zen master Dokushô Villalba on December 27, 2021, without any editing. Maybe if one day I decide to make this official, I'll add some music and an intro. If you keep scrolling, you can read a little more about this project.

Soy un asiduo oyente de podcasts. Es uno de mis formatos y compañero favorito en viajes y horas de retoque. Cómo soy una persona que se aburre con facilidad y que se puede pasar horas divagando en futuros proyectos, durante unos meses me plantee seriamente —por si no había ya suficientes— que podría ser interesante hacer un podcast. Este proyecto tendría un enfoque similar al de esta newsletter: un espacio algo ecléctico, donde poder dialogar con personas que me interesan sobre una amplia variedad de temas. La excusa perfecta para conocer y charlar con personas que, de otra manera, es más complicado sacar tiempo y ganas. También poder practicar el arte de la conversación y, sobre todo, aprender a escuchar, algo de lo que suelo pecar a menudo.

Tenía ya mis primeros invitados: Fernando y Pedro Caruncho, jardinero y arquitecto del cual hablé ya anteriormente en esta newsletter. Pero, por desgracia, el día anterior a la grabación, me dio un cólico nefrítico y tuve que cancelar el encuentro. A punto estuvimos de hacer un segundo intento pero no pudimos cuadrar agendas.

Barajé varios nombres para el podcast. Finalmente, me dicidí por mushotoku, y ¿qué significa esta extraña palabra? Voy a intentar definirla, no sin antes dar un pequeño rodeo.

Mi fascinación por el Budismo Zen ha ido en aumento desde finales de 2020, llevándome a sumergirme en la práctica de meditación o zazen, participar en retiros y encontrar una profunda conexión con su “filosofía” y estética. Lo que verdaderamente distingue al zen de otras prácticas espirituales es su llamada a vivir la experiencia directamente, sin filtros intelectuales, y su habilidad para integrarse en lo cotidiano. La iluminación no se busca exclusivamente en la quietud de la meditación; cada momento, ya sea lavando platos, comiendo, tomando fotos o incluso las visitas al retrete, se convierten en una oportunidad para practicar la atención plena. En esta tradición, no existe un momento más sagrado que otro: solo existe el ahora, invitándonos a vivir plenamente en cada instante.

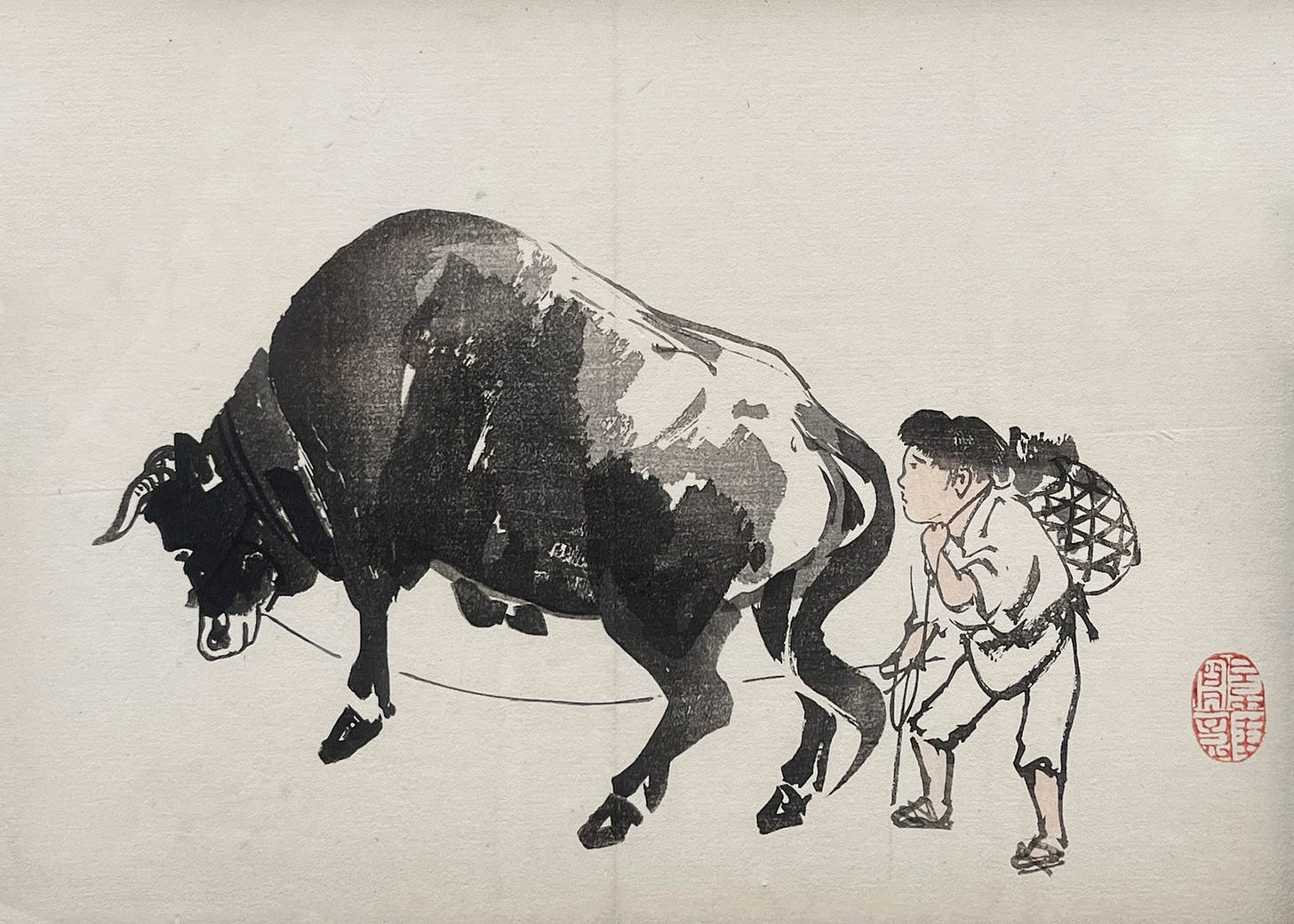

Poco a poco uno va integrando la práctica y cada vez surge de una manera más natural en distintos ámbitos de la vida. La idea es desembarazarse de ideas y conceptos, simplemente Ser o como ellos dicen, alcanzar la naturaleza original o de Buda. No es un camino fácil. La tarea de domar la mente o el buey —como la suelen describir metafóricamente— puede tomar toda una vida y más en el ambiente frenético y enfermizo en el que vivimos.

Pero… ¿por qué el zen? Pienso que nuestra generación se siente huérfana de espiritualidad, un vacío que intentamos llenar con un montón de sucedáneos, casi todos pervertidos por el consumismo y la superficialidad. En Occidente —y creo que también en parte de Oriente— algunos hemos sustituido nuestra espiritualidad por el materialismo, otros por el new age, la tecnología, las drogas, las redes sociales… cualquiera de sus formas busca la gratificación constante e inmediata. Estos sustitutos, lejos de proporcionar una verdadera conexión con nuestro ser interior o con una comunidad de creencias compartidas, a menudo nos dejan sintiéndonos más vacíos y desconectados.

Hablando a nivel español, el catolicismo, aunque conserva cierto poder en las élites, ha perdido gran parte de la influencia que tenía en nuestra sociedad —persistiendo oculto en muchas otras ideologías—. Ahora no es más que una especie de zombie. Nos quedan sus magníficas catedrales, la quietud de los claustros, sus perdidas ermitas, pero ya casi son solo cáscaras vacías, si no ya ruinas.

Personalmente, a pesar de haberme criado bajo su influencia, siempre he tenido dificultades para identificarme con el catolicismo. Aunque entiendo y, en cierta medida, puedo compartir el mensaje simbólico de Cristo, siento que la Iglesia se ha reducido a una estructura de moral y tradición que olvida la búsqueda de una conexión profunda y directa con lo absoluto. En el cristianismo, así como en las demás religiones abrahámicas, la mística siempre ha mantenido una relación complicada con el establishment eclesiástico. Además, estas religiones enseñan que existe una separación entre el hombre y la naturaleza, privilegiando al primero, un pensamiento que me parece totalmente erróneo. Este enfoque, heredado por la Ilustración, aún mejorando nuestra calidad de vida a través de la tecnología y avances científicos, nos ha conducido al desastre ecológico actual.

Estas divergencias me llevaron, como a muchos otros, hacia el ateísmo, bajo la premisa de que la razón puede brindarnos todas las respuestas; relegando así cualquier forma de religión o espiritualidad a meros remanentes de un pensamiento arcaico que debería extinguirse en favor del progreso.

Sin embargo, mi encuentro con el Budismo Zen y otras tradiciones espirituales orientales, como el Taoísmo o el Samkya, han marcado un punto de inflexión. En estas prácticas no se postula la existencia de un Dios personal, ni se ofrecen respuestas definitivas o certezas inmutables. En su lugar, te invitan a explorar y vivir sus enseñanzas por uno mismo. Esta apertura ha generado en mí la reflexión de que, para quienes en Occidente venimos de un enfoque materialista y ateo, estas prácticas ofrecen un camino viable hacia la reconexión con ese deseo innato de trascendencia. Más aún, considero que se convierten en un puente hacia la búsqueda de los aspectos olvidados de nuestra propia herencia espiritual, evidenciando que, a pesar de haber perdido contacto con gran parte de este antiguo conocimiento, aún reside entre nosotros, esperando ser reencontrado.

Y después de toda esta parrafada… ¿qué significa la palabra japonesa mushotoku (無所得)? Significa literalmente ‘nada que obtener’ pero que se podría también traducir como 'hacer algo sin esperar ningún beneficio personal’, algo de lo cual solemos pecar en Occidente, siempre en búsqueda de un resultado.

Procedente del Sutra de la Gran Sabiduría, es una actitud fundamental en el zen. También en la India, existe una noción parecida conocida como Karma-Yoga, introducida en la Bhagavad Gita, donde la esencia radica en la acción misma, y se enfatiza la importancia de desapegarse de los resultados de dichas acciones.

Pero esta palabra tiene un significado aún más profundo. Mejor que sea el maestro zen Dokushô Villalba —a quien presentaré más adelante— quien nos introduzca de primera mano con estos extractos tomados de una entrada en su sitio web dedicada a este concepto:

Aunque crea que tengo un yo, un cuerpo, un hijo, una casa, una compañera, una sangha, un monasterio, discípulos y seguidores… aunque crea haber obtenido fama y reconocimiento… aunque cierre los puños y agarre dos puñados de arena… lo único real es mushotoku, nada que obtener.

Todos mis logros son mushotoku: algo que no poseo, algo que no he obtenido ni podré obtener nunca. Son fukatoku (不可得), algo ‘imposible de obtener’, como afirma otra expresión zen.

No se trata de que no debamos buscar el provecho personal. Mushotoku no es un imperativo ético, no es un precepto ni una admonición. Es la constatación de la realidad. La realidad es fukatoku: inaprensible. Aunque creamos haber obtenido algo, eso que hemos obtenido es solo una ilusión, un sueño del que tarde o temprano despertaremos. Usualmente tarde ya, en el umbral de la muerte.

Adoptar esta perspectiva va más allá de actuar sin esperar nada a cambio, de vivir al estilo carpe diem sin preocuparse por el futuro; implica el memento mori —recuerda que morirás—, tener siempre presente que todo lo que hacemos es en vano. Sin embargo, lejos de adoptar una actitud derrotista y caer en el nihilismo, reconocer la muerte como parte de nuestra esencia es fundamental. Debemos mantenerla presente e interiorizarla. Como bien continúa explicando el maestro:

Esta realidad puede producirnos congoja y aflicción, pérdida de sentido y desmotivación. Pero también, si tomamos clara conciencia de que ‘así es como es’, y lo aceptamos desde el fondo de nuestro corazón, podemos liberar nuestro espíritu de todas las redes y los obstáculos, de las causas mismas de los obstáculos. Podemos vivir cada día sin miedo ni temor, sin causas del miedo y del temor. Podemos liberarnos de todas las perturbaciones, de las ilusiones y de los apegos y experimentar en vida la etapa última de nuestra peregrinación: la paz interior. Este es el camino que han seguido todos los Budas.

Ahora, siento que mushotoku no es un buen nombre para un podcast. He intentado buscar otra palabra que pueda significar algo parecido, pero en español no he encontrado nada que me acabe de gustar. La inclusión de una palabra japonesa en un contexto de podcast en español corre el riesgo de trivializarse, como ya lo ha hecho la propia palabra zen. Hay peluquerías, hoteles o comida para perros zen, y otras japonesas como wabi sabi o ikigai, que de tanto usarse en forma de marketing acaban por generar cierto rechazo. Solo hay que echar un vistazo a la sección de autoayuda de las librerías. Es algo que me preocupa bastante: traer una idea de Oriente y pervertirla como ya hemos hecho con tantas otras tradiciones.

Y así llegamos a la que sería mi primera y única conversación de este proyecto, la que tuve a finales de diciembre de 2021 con Dokushô Villalba (Utrera, 1956) en el Templo Luz Serena, ubicado en el Parque Natural Las Hoces del Cabriel, cerca de Requena (Valencia).

Destacado referente del zen en España y discípulo de Taisen Deshimaru y Shuyu Narita, fundó el Templo Luz Serena en 1987, el primer monasterio zen de tradición Soto en el país, contribuyendo significativamente a la difusión del Budismo Zen. Además de su labor como fundador y divulgador, es reconocido como escritor y traductor de numerosos libros, entre los cuales destacaría ‘El Zen en la plaza del mercado’ o la traducción del ‘Shôbôgenzô’ de Eihei Dōgen —quien trajo en el s.XIII el Soto Zen desde China a Japón— ambos editados por la editorial Kairós.

Lo descubrí a través de otro podcast, el de Álex Fidalgo, en un momento de profunda crisis existencial, justo cuando había empezado a interesarme por las obras de Alan Watts o D.T. Suzuki; su mensaje llegó en un momento crucial. A partir de esa escucha, inicié un curso online de meditación y participé en un retiro en el templo Luz Serena así como leído varios libros suyos sobre Budismo Zen y pensamiento oriental.

Estuve nervioso durante toda la conversación; me quedé en blanco en numerosas ocasiones y me costó mucho conectar ideas para hacer la charla más fluida. Probablemente no me preparé lo suficiente y confié demasiado en la improvisación. Al escuchar el resultado, decidí archivarlo hasta hoy, cuando he pensado que este formato, en el que experimento con otras formas de comunicarme, podría ser adecuado. Desde que el zen entró en mi vida, uno de mis objetivos, sobre todo en fotografía, ha sido desaprender para volver a tener una mente de principiante, mirar el mundo con los ojos de un niño, tal como lo hice en 2007 cuando por primera vez una cámara cayó en mis manos y comencé a ver el mundo a través del visor. Este espacio es precisamente para eso: seguir mi curiosidad, jugar, probar cosas sin miedo al qué dirán, a los 'likes', a salir de mi zona de confort, a fallar, y hacerlo sin buscar una razón ni un objetivo concreto, simplemente estoy aquí. Escribiendo todo esto sin saber muy bien por qué. Shunryu Suzuki, maestro Zen y autor del clásico libro sobre la vía 'Mente Zen, mente de principiante', enfatiza esta idea al decir: 'En la mente del principiante hay muchas posibilidades, pero en la del experto hay pocas'.

Aún con la impresión de caos que me genera la conversación y la vergüenza que me doy al escucharme, creo que salieron algunos puntos interesantes.

Esta conversación fue la última que Dokushô realizó antes de un año sabático donde focalizó en la creación y mejora del ‘Campus Virtual Soto Zen’ y la ‘Escuela de Atención Plena’. Dos importantes y muy recomendables plataformas para entrar en contacto o profundizar en estas disciplinas.

Solo queda agradecer a Dokushô Villalba el tiempo que me dedicó aquella mañana y la ayuda que ofrece, directa o indirectamente, con todo el conocimiento que difunde por la red. No tengo claro qué acabará pasando con este podcast: si lo pondré en marcha, si seguirá con el mismo nombre, cambiará o seguirá guardado en el cajón. De momento, dejo esto por aquí. Dejarlo en un disco duro me parecía de mala educación hacia el maestro.

Para aquellos interesados en profundizar en el tema, además de los libros mencionados anteriormente, estas son algunas lecturas iniciales que encontré muy útiles. Gracias Álex, por ayudarme a abrir esta puerta, sin puerta.

’Preguntas a un maestro zen’ Taisen Deshimaru

’El camino del zen’ y ‘¿Qué es el Tao?’ Alan Watts

‘Zen’ por Michel Bovay, Laurent Kaltenbach, Evelyn de Smedt

’Apologia del Taoísmo’ Giuseppe Tucci

‘El zen y la cultura japonesa’ D.T. Suzuki

’El zen y el tiro con arco’ Eugen Herrigel

‘El libro del té’ Kakuzo Okakura

’Notas desde mi cabaña de monje’ Kamo No Chomei

I'm a regular podcast listener. It's one of my favorite formats and companions for travel and editing hours. As someone who easily gets bored and can spend hours daydreaming about future projects, I seriously considered for a few months— as if there weren't enough podcasts already— that creating a podcast could be interesting. This project would have a similar approach to this newsletter: an eclectic space where I can have conversations with people who interest me on a wide variety of topics. The perfect excuse to meet and chat with people who otherwise it would be more challenging to find the time and motivation to engage with. Also, to practice the art of conversation and, above all, learn to listen, something I often struggle with.

I already had my first guests, Fernando and Pedro Caruncho, a gardener and architect I've talked about previously in this newsletter. Unfortunately, the day before the recording, I suffered from nephritic colic and had to cancel the meeting. We were close to making a second attempt, but we couldn't align our schedules.

I considered various names for the podcast but finally settled on mushotoku, and what does this strange word mean? I'll try to define it, but first, let me take a small detour.

My fascination with Zen Buddhism has been growing since the end of 2020, leading me to dive into meditation or zazen practice, participate in retreats, and find a deep connection with its "philosophy" and aesthetics. What truly distinguishes Zen from other spiritual practices is its call to live the experience directly, without intellectual filters, and its ability to integrate into daily life. Enlightenment is not sought exclusively in the stillness of meditation; every moment, whether washing dishes, eating, taking photos, or even visiting the toilet, becomes an opportunity to practice mindfulness. In this tradition, no moment is more sacred than another: only the now exists, inviting us to live fully in each instant.

Gradually, without realizing it, you integrate the practice, and it emerges more naturally in different areas of life. The idea is to rid oneself of ideas and concepts, simply to Be or, as they say, to reach Buddha's original nature. It's not an easy path; taming the mind or the ox—as it's metaphorically described—can take a lifetime and more in the frenetic and sick environment we live in.

But why Zen? I think our generation feels orphaned of spirituality, a void we try to fill with a bunch of substitutes, almost all perverted by consumerism and superficiality. In the West—and I believe also in much of the East—some of us have replaced our spirituality with materialism, others with new age, technology, designer drugs, social media, and a constant search for immediate gratification. These substitutes, far from providing a true connection with our inner selves or with a community of shared beliefs, often leave us feeling emptier and more disconnected.

Catholicism, although it retains some power among the elites, has lost much of the influence it had in our society—but persists hidden in many other ideologies—now it's just a kind of zombie. We are left with its magnificent cathedrals, the quiet of the cloisters, its lost hermitages, but they are almost just empty shells, if not ruins.

Personally, despite having been raised under its influence, I have always struggled to identify with Catholicism. Although I understand and, to some extent, can share the symbolic message of Christ, I feel that the church has been reduced to a structure of morals and tradition that forgets the search for a deep and direct connection with the absolute. In Christianity, as well as in other Abrahamic religions, mysticism has always had a complicated relationship with the ecclesiastical establishment. Moreover, these religions teach that there is a separation between man and nature, privileging the former, a thought I find completely erroneous. This approach, inherited from the Enlightenment, while improving our quality of life through technology and scientific advances, has led us to the current ecological disaster.

These divergences led me, like many others, towards atheism, under the premise that reason can provide us with all the answers; thus relegating any form of religion or spirituality to mere remnants of archaic thought that should be extinguished in favor of progress.

However, my encounter with Zen Buddhism and other Eastern spiritual traditions, such as Taoism or Samkhya, has marked a turning point. In these practices, the existence of a personal god is not postulated, nor are definitive answers or immutable certainties offered. Instead, they invite you to explore and live their teachings for yourself. This openness has led me to reflect that, for those of us in the West coming from a materialistic and atheistic approach, these practices offer a viable path towards reconnecting with that innate desire for transcendence. Furthermore, I consider them to be a bridge to the search for the forgotten aspects of our own spiritual heritage, showing that, despite having lost contact with much of this ancient knowledge, it still resides within us, waiting to be rediscovered.

And after all this long explanation, we finally arrive at mushotoku (無所得), a Japanese word with a meaning I find particularly beautiful and scarce in the West. It means something like 'acting without seeking benefit'. Originating from the Sutra of Great Wisdom, it's a fundamental attitude in Zen. In India, there's a parallel notion known as Karma-Yoga, introduced in the Bhagavad Gita, where the essence lies in the action itself, and the importance of detaching from the outcomes of such actions is emphasized.

However, it would be better for Zen master Dokushô Villalba —whom I will describe in detail later— to introduce us firsthand with these excerpts taken from an entry on his website dedicated to this Japanese word:

Even if I believe I have a self, a body, a son, a house, a partner, a sangha, a monastery, disciples, and followers... even if I believe I have gained fame and recognition... even if I clench my fists and grab two handfuls of sand... the only real thing is mushotoku, nothing to obtain.

All my achievements are mushotoku: something I do not possess, something I have not obtained and will never be able to obtain. They are fukatoku (不可得), something 'impossible to obtain', as another Zen expression states.

It's not about not seeking personal gain. Mushotoku is not an ethical imperative, not a precept or admonition. It is the acknowledgment of reality. Reality is fukatoku: ungraspable. Even if we believe we have obtained something, what we have obtained is just an illusion, a dream from which we will sooner or later awaken. Usually too late, on the threshold of death.

Adopting this perspective goes beyond acting without expecting anything in return, living in a carpe diem style without worrying about the future; it implies memento mori—remember you will die—always keeping in mind that everything we do is in vain. However, far from adopting a defeatist attitude and falling into nihilism, recognizing death as part of our essence is crucial. We must always keep it in mind and internalize it. As the master continues to explain:

This reality may cause us anguish and affliction, loss of meaning, and demotivation. But also, if we take clear awareness that 'this is how it is', and accept it from the bottom of our hearts, we can free our spirit from all the nets and obstacles, from the very causes of the obstacles. We can live each day without fear or dread, without the causes of fear and dread. We can free ourselves from all disturbances, illusions, and attachments and experience in life the ultimate stage of our pilgrimage: inner peace. This is the path followed by all Buddhas.

Now, I feel that mushotoku is not a good name for a podcast. I've tried to find another word that might mean something similar, but in Spanish, I haven't found anything that I really like. Including a Japanese word in a Spanish podcast context runs the risk of becoming trivialized, as has the word Zen itself. There are Zen hair salons, hotels, or dog food, and other Japanese words like wabi sabi or ikigai, which, from being used so much in marketing, end up generating certain rejection. Just take a look at the self-help section of bookstores. It's something that concerns me a lot: bringing an idea from the East and perverting it as we have done with so many other traditions.

And so we come to what would be my first and only conversation, which I had at the end of December 2021 with Dokushô Villalba (Utrera, 1956) at the Luz Serena Temple, located in the Las Hoces del Cabriel Natural Park, near Requena (Valencia).

A prominent figure of Zen in Spain and disciple of Taisen Deshimaru and Shuyu Narita, he founded the Luz Serena Temple in 1987, the first Zen monastery of the Soto tradition in the country, significantly contributing to the spread of Zen Buddhism. In addition to his work as a founder and popularizer, he is recognized as a writer and translator of numerous books, among which 'Zen in the Market Square' or the translation of 'Shôbôgenzô' by Eihei Dōgen—who brought Soto Zen from China to Japan in the 13th century—both published by Kairós.

I discovered him through another podcast, that of Álex Fidalgo, at a time of deep existential crisis, just when I had started to take an interest in the works of Alan Watts or D.T. Suzuki; his message arrived at a crucial moment. Following that listening, I started an online meditation course and participated in a retreat at the Luz Serena temple as well as read several of his books on Zen Buddhism and Eastern thought.

I was nervous throughout the conversation; I blanked out numerous times and struggled to connect ideas to make the talk flow better. Probably, I didn't prepare enough and relied too much on improvisation. Listening to the result, I decided to archive it until today, when I thought that this format, in which I experiment with other ways of communicating, could be suitable. Since Zen entered my life, one of my goals, especially in photography, has been to unlearn in order to have a beginner's mind again, to look at the world with the eyes of a child, just as I did in 2007 when a camera first fell into my hands, and I began to see the world through its viewfinder. This space is precisely for that: to follow my curiosity, to try things without fear of what people will say, of 'likes', of stepping out of my comfort zone, of failing, and to do it without seeking a reason, just being here; writing all this without knowing quite why. Shunryu Suzuki, Zen master and author of the classic book on the path 'Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind', emphasizes this idea by saying: 'In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert's there are few'.

Even with the impression of chaos that the conversation generates for me and the embarrassment I feel listening to myself, I believe some interesting points came out. We talked about Zen, reality, meditation, awakening, ego, meaning, photography, social networks...

This conversation was the last one he had before taking a sabbatical year to focus on creating and improving the 'Soto Zen Virtual Campus' and the 'Mindfulness School'. Both are important and highly recommended platforms for those looking to get in touch with or delve deeper into these disciplines.

All that remains is to thank Dokushô Villalba for the time he dedicated to me that morning and for the help he offers, directly or indirectly, with all the knowledge he spreads online.

I'm not sure what will happen with this podcast: whether I will launch it, if it will continue with the same name, change, or remain stored away. For now, I leave this here. It seemed rude to the master not to.

For those interested in delving deeper into the subject, in addition to the books mentioned earlier, these are some initial readings I found very useful. Thank you, Álex, for helping me open this door.

'Questions to a Zen Master' Taisen Deshimaru

'The Way of Zen' and 'What is Tao?' by Alan Watts

'Zen and Japanese Culture' D.T. Suzuki

'Zen in the Art of Archery' Eugen Herrigel

'The Book of Tea' Kakuzo Okakura

'Hojoki' Kamo No Chomei